In our third year of architecture (in ’92-’93), we were informed that it was expected from us to make a selection of all the areas offered to us to do scientific research on, as a substitute for a conventional thesis.

In the summer of ’93 we set of for India for the first time, without knowing quite well what to expect of it and without having a clear idea on what research to do there or how to go upon it.

Upon arrival in Bombay, it became directly clear that this definitely is another world! But enthusiast as we were, we started immediately to explore this so exiting country with its fantastic people and so a different way of life and mentality.

Bangalore was to be our “home post” from where to conduct all kinds of explorations. I joined the group anthropological-architectural research, under guidance, teaching and counselling of prof. Fried Verschuren en Marc Dujardin.

Part of this group was selected to transform the experien

ce of the teaching, seminars, models, reading, etc, into real field research work.

“Architectural Anthropology starts with the idea that every human society builds their habitat in a way which on the one hand reflects the ecosystem, technology, mode of production, and ideas about life and after-life of that particular society, while on the other hand it articulates in its particular forms what is a universal phenomenon inherent in any human society.”

(Jan Pieper, 1980, Outline of architectural anthropology)

The Hindu tradition reaches a climax during the Gupta period (6th century AD), that marks the classical body of Sanskrit literature (the great epics like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana) and the appearance of many scientific disciplines (Vastu Vidya). By the end of this Gupta period that we can detect that different structures at different geographical locations were based on the same definite underlying principles supported by an own distinct visual language. These principles are part of the Vastu Shastra, the science of building.

As all sciences, also the ethos of traditional architecture was rooted in the brahmanical ideas-cosmology-theory of creation-space & time dynamics-man’s place in nature. According to the Hindu concept, ’the cosmos is a manifestation of a transcendent, non-dual, yet immanent principle, which unfolds the world and inhabits it as its animated principle. The one, undivided principle is known as Brahma Purusha, or cosmic being.

We were so fascinated by the strong cultural Hindu influence, that we decided upon our topic to research the impact of Vastu Shastra on the nowadays way of living, building, and organization of space.

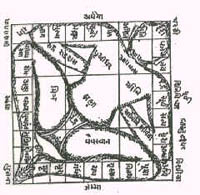

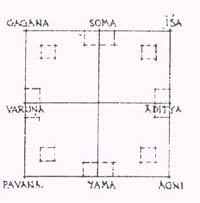

The Vastupurusha Mandala is a square yantra, a diagram, representing the ritual form of the vastupurusha. It seeks to represent the macro-cosmos, the essence of all things, the supreme being, the Purusha. The mandala is devided into different padas or divisions. Each of these padas represents a god that holds down a part of the demon so that he will never rise again. The Vastapurusha requested the Supreme principle, who is known as Brahma Santha, to always occupy the centre of his being, the nabhi or navel. The encircling padas or divisions are hence occupied by lesser deities who form a hierarchy. Around it, in the border of the mandala, divinities preside over solistial and equinoctial points. The eight cardinal directions are presided over by the eight planets. In this way, the mandala symbolically represents an image of sacred space and cyclic movement of time, measured by the day, month, year and wider cycles of the eclipses. In this way, the mandala embodies an all-inclusive, contained image of the ordered cosmos.

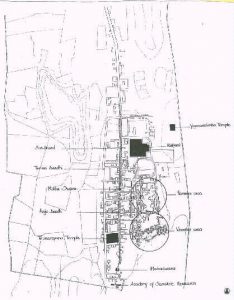

Melkote, being a small town, but a local sacred place in Karnataka, still is very traditional and orthodox.

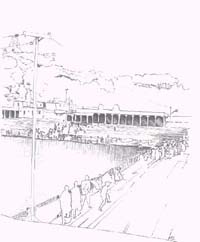

A charming town where the Yoganarashima temple linked with the Kalyani-complex, and the Tirunarayana temple have been dominating its history and present.

Melkote and the Tirunaranyana temple are intimately associated with the history and affairs of Sri Vaishnavism (a system based upon complete surrender to the God Vishnu.) Hence, the Brahmin community are of great influence and importance.

The major road of the town, Raja Beedhi (Royal Street, since it serves as path for temple processions), is laid out in such a way, to lead directly to the front of the Tirunarayana temple, running perfectly from North to South. Parallel with it, Terina Beedi (car street).

Raja Beedi, Tirunarayana temple, Yoganarashima temple and Kalyani form the core area around which the town is structured. This section is (mainly) inhabited by Brahmins.

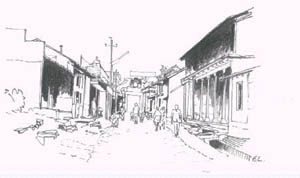

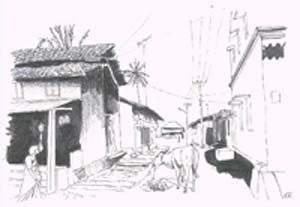

Walking on the south part of Melkote, east off Raja Beedi, you end up in the labyrinth of th weavers’ community. In contradistinction to Raja Beedi, where the houses are neatly built next to each other, the weavers area seemed a spontaneously grown community. Veering streets, common places, the sudden widening and narrowing, the surprising turns, squares, the clusters,… all add to create a fascinating surrounding. The farmers community is situated to the North of the weavers area, also east off Raja Beedi.

Another important aspect of the layout of this settlement is the hierarchy of spaces. From Raja Beedi, the public realm, secondary streets start off and enter the private realm of the settlement, meandering through it and ending up in clusters of dwellings.

The labyrinth of the weavers community is not as chaotic as it seems at first. There definitely is a very clear hierarchy of spaces and a gradient from public into most private. From Raja Beedi and the centre with the temples and Kalyani(public-public), into the side-streets (public) leading to the little narrow foot-walkways with its clusters of dwellings (semi-public), to the jagali (semi-private), into the house (private-private) The hierarchy is also respected by the people of Melkote. If you don’t live in the farmers or weavers community, you will most likely not enter that neighborhood.

Cotton Beedi, is the only ‘street’-like, ‘wide’ way through the weavers community.

Cotton Beedi, is the only ‘street’-like, ‘wide’ way through the weavers community.

In a cluster of dwellings, the house is extended onto the street. A lot of activities take place on the street. In this hierarchical system where the house/dwelling belongs to the cluster-footway, the footway belongs to a larger fabric that belongs to a larger fabric, belonging to the whole. So each dwelling has a defined place of its own.

Since the plan available of Melkote was only so and so accurate and only so for the core area around Raja Beedi, we decided to update that part to our best, without having to mesuring this entire section. Our interest lay in the weavers community since this area seemed to have an interesting structure (similar to a labyrinth at first, but later on discovering it not to be quite so chaotic), and the most interesting, still traditional and old houses. As a consequence of having no plan at all to work with, we discovered our way through the weavers area without getting lost and started measuring-up this area of about houses, in detail, including stones, fences, trees, green, walkways, water points, etc.

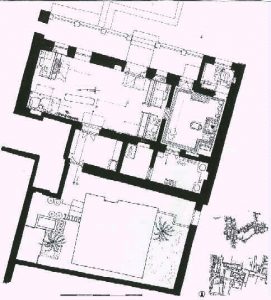

Out of this entire area, we made a selection of 8 houses to be measured-up in detail and studied. One is shown here. This house has 6 inhabitants, the husband and wife, his son with his wife and 2 children. The women also keep busy weaving. There used to be 4 weaving-looms in the living-room, but nowadays only 3 are still used. The husband’s brother, who’s living next door with his wife and children, also comes weaving in this living-room.

The 2 houses are built against each other, they are a whole. Behind the house, a new, small house is built. The grandfather is sleeping here, but during the day, he spent most of his time with his family. This house is also used for storage.

Doing four steps up you come on a small platform on the jagali in front of the door. Next to the entrance door, there are two small niches, for oil-lamps. The rest of the jagali is on a higher level. The jagali is covered with wooden planches and the loft above is closed-up with bamboo-poles.

To enter the living room, on the same level of that small platform, you have to step on a stone- and over a wooden doorframe. The floor is hard-packed earth, while at the doors in the living room, there are flat stone slabs in front. The living room is also working place with 3 weaving-looms (formerly 4) and used for sleeping as well. Picture frames are hanging opposite the main entrance door. There are 3 windows at the front side, 2 of them situated right next to a weaving-loom. The ceiling is totally covered with wooden planches, except where one weaving-loom extends with its strings-, blocks-, … construction into the loft.

On the left side in the living room, there is a door (you step over the doorframe) to the dining-(sleeping-)room. There is a colored strip along the walls, going around the mash-pit and the base of the stairs. These stairs are constructed in such a way that when you take the first step on the stone base, you face E (according to Vastu-building-laws). The wooden staircase (facing N) takes you up to the loft. There is no window in this room, but there is an entrance-door leading to the jagali, going through the doorframe and one step up on the jagali itself. The ceiling is closed with wooden planches, except for the staircase going up.

From the dining-room, you go into the bathroom without level-difference. The bathroom, built on the jagali has one window on the front. The ceiling is covered with planches.

At the other side of the dining-room, you enter the kitchen by taking a step up over a stone and wooden door frame. In the dining-room, the door to the kitchen and the door to the jagali are in sequence. You can only enter the puja-room from inside the kitchen. Both of them have no windows and their ceilings are covered.

From the living-room you enter the storage, going up one step and over the wooden doorframe. The storage-room has no windows, but there is a back-entrance door that is in sequence with the living room door but not with the main entrance door.

Going one step up and through the wooden doorframe, you step outside in the walled-in private backyard. It also has a side-entrance. There, the grandfather of the family lives in the small new house. Two toilets and a water-recipient are situated in the SW corner of the backyard.

- The main entrance-door is situated in the middle of the front.

- The openings in the front have no particular modulation.

- The rest of the house is built with the same module.

- This module (1) is used as the distance between the columns on the jagali, but the distance between the columns on the left and the right of the door is a little bit more than the module.

- The depth of the jagali (1) is 1/5 of the total depth of the house.

- The columns supporting the wooden truss are at equal distance (B).

- The stud of the roof is situated halfway the total depth of the building (A).

- H = height of the living room + height beam

- The height of the jagali (including the beam) equals the height of the loft, up to the wooden truss (4/5 H).

- Standing in front of the house, the proportion of the roof part and the height of the jagali up to the beam, as well as the proportion of the drawing and the front wall up to the end of the thick plastering are equal. (H-4/3H , t-4/3t)

- The jagali is on a higher level than the living room but the platform leading up to the front door is on the same level as the living room.

- The back part of the house (storage – puja – kitchen) is situated on a higher level.

- The backyard, once more is on a higher level.

- The wooden columns on the jagali are decorated and placed on a stone slab.

- The slope of the roof is constant.

We studied the orientation of the elements (drawings in original report):

NE bathroom : stove>S – 2nd entrance

E dining – sleeping when weaving

SE kitchen : stove>W

S sleeping>S – puja>E

SW storage – back entrance – garden – toilet

W (part of neighbour’s house) – sleeping>W

NW well

N main entrance – jagaliWeaving: 3 presently : >E , >W , >W : light from N

1 formerly : >E : light from N! > direction in which:

H/D/L

jagali:1.32/1/6.03

living room:0.57/1/2.25

dining:0.57/1/0.88

living + dining:0.57/1/3.19

kitchen:-/1/1.74

puja:-/1/0.85

bathroom:1.39/1/1.20

storage:1.18/1/1.63

We studied the proportions of the elements (drawings in original report):

house:0.50/1/1.42

These numbers are the proportions of the height, depth, length of the inside measurements of each room. The depth is always taken equal to 1, so that the proportions would be better comparable. We always took the average measurement of each distance because the houses are not perfectly perpendicular. All numbers are rounded up to two decimals. If the proportions are more or less definite, we took it for granted that it was meant to be a clear proportion.

0.22 – 0.28 -> 1/4

0.30 – 0.36 -> 1/3

0.47 – 0.53 -> 1/2

0.64 – 0.70 -> 2/3

0.72 – 0.78 -> 3/4

-

The length of the jagali is 6 times the depth.

-

The length of the living room is 2+1/4 the depth.

-

The length of the kitchen is 1+3/4 the depth.

-

The height of the house is 1/2 the depth.

After studying all the elements of the house, with its orientation and proportions, we then compared each element of the 8 houses as a whole, regarding their orientation and proportion.

(with comparative drawings in original report)

Two are described below:

ORIENTATIONS AND PROPORTIONS OF THE HOUSES

- From the 8 houses we measured, 5 are facing a good direction according to Vastu. Because the weaver’s area is so organically developed, it has houses in all directions. We decided to choose 8 houses to measure, facing different directions in order to attain a more or less representative idea. Our general impression was that more houses are facing N – E than S – W in the weavers area.

- We saw that 7 of the 8 houses have a jagali higher than the living room. This is very logic considering that the jagali is not only the outside-extension of the house, but also a pre-entering-space that keeps away the dust, the glare, the rain and the sun.

- It is clear that certain proportions are used in the measurements of the jagali itself, especially the depth of the jagali in relation to the depth of the house and the proportions of the house seen standing in front of it. These proportions differ in all houses.

PUJA ROOMS

- house 31 in W, puja facing E

- house 26 in S, puja facing NE

- house 46 in S, puja facing E

- house 42 in E, puja facing W

- house 43 in SW, puja facing E

- house 61 in E, puja facing E

- house 62 in SW, puja facing E

- house 70 in SE, puja facing E

In all the houses we measured, the puja-closet was never situated in the NW, N, NE side of the house. In 6 of the 8 houses the puja was facing E ( house 26 : facing NE +- , house 42 : facing W — ).

GENERAL CONCLUSION:

‘Even when I build a house, I don’t care about those rules’.

this was said to us by the Sanskrit Academy Director of Melkote, M.A. Lakshmi Tathachar, during an interview with him.

But we saw that, to a certain extend, Vastu still lives (in these 8 houses of the weavers community of Melkote, we measured-up).

Especially things most related to their religion are still strongly influenced by Vastu Building Science.(as are: puja, kitchen, sleeping, and water parts).

The entire study is called:

“VASTU EXPRESSIONS IN A SOUTH INDIAN TEMPLE-TOWN”

Case-study: The weaverscommunity of Melkote.

by:

Ellen Leijskens

Dominique Vieren

St. Lucas Gent, Belgium

5th year of architecture

1994-95

The original thesis-report consists of 239 pages, A3 size.

This summary and internet-application is made by Ellen Leijskens.

Total copyright needs to be respected.

For more information, please contact me.